‘Nobody in England had written such a book as The Old Wives’ Tale in such a way. It had not the exuberance of Dickens; nor the ironic sentiment of Thackeray. It was less brilliant than Meredith and less nobly tragic than Hardy. But, on the other hand, it had a warmth and kindness quite foreign to any realists known to the English public. It was praised and loved; and was thereafter the touchstone by which all Bennett’s work was judged.’ Frank Swinnerton, Biography

I wish I were a graphologist who could analyse handwriting, and signatures, in particular. I am looking at Arnold Bennett’s (below) at the moment as I have been having a wonderful Bennett readathon while recovering from flu. It was sheer delight to sit and read for hours, immersed in a world full of clerks and drapers, shopkeepers and streetwalkers, valets and lawyers, tobacconists and landladies, and be deeply moved by his characters’ struggles to find happiness, love, and contentment, as well as facing their own mortality in such circumstances as illness, accident, murder and warfare.

He has the ability to shock; his description of a guillotining in Paris is not for the faint-hearted. He wrote unbearable scenes of sadness and dying. I defy anyone not to cry at a scene towards the end of the The Old Wives’ Tale when Sophia visits Gerald Scales, her estranged husband of thirty years, on his deathbed.

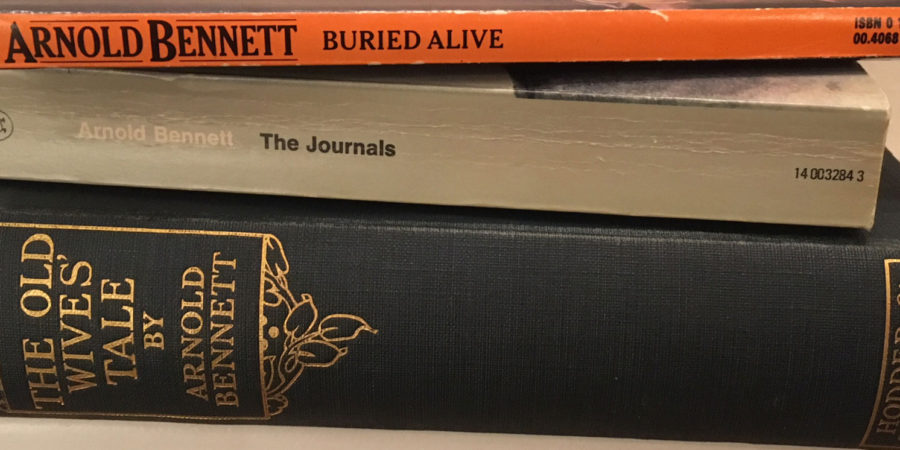

Perhaps I don’t need someone to interpret Bennett’s signature. It’s a magnificent, steady, bold hand with flourishes. I think I can guess what sort of man he was from having read The Old Wives’ Tale, Buried Alive and Riceyman Steps, one after the other, this week, as well as dipping into his Journals. He was incredibly hard working, was one of the most popular authors of his time and became very wealthy from his writing. He was an attractive man, confident (having overcome his stammer as a child) and worldly. He liked the good life but was generous with his money. He also suffered from terrible neuralgia, migraines and digestive problems.

Bennett wrote beautifully, deeply and wittily about people, places and the way we live our lives. He had a wider perspective of life than many contemporaries, reaching far beyond the Potteries where he was born, living in France for nine years., travelling in America. He was very well-read and was steeped in the great French writers such as Balzac, Flaubert and Zola.

In addition, he edited magazines, wrote stage plays which were big hits in London, filmscripts, and was director of propaganda for the Ministry of Information in 1918. And he kept a journal all his working life – amounting to over a million words.

I’m looking back a 110 years to 1908. A very good year for Arnold Bennett – both a productive and lucrative year of writing. He always liked to record his output and income at the end of each year, recorded in his journals. ‘I have never worked so hard as this year and I have not earned less for several years but I have done fewer sillier things than usual.’

In 1908 he wrote Buried Alive, three quarters of of The Old Wives’ Tale, [total word count = 200,000] three other books, half a dozen short stories and over sixty newspaper articles. Arnold Bennett’s total word count for that year was 423,500 words.

At the end of 1912 Bennett recorded his earnings that year as £17,600 – equivalent to £1,890,878 today. He had five of his plays performed too which boosted his royalties, no doubt. He bought a car, a yacht, and a house that year. Not bad for a scribbler!